Talking with young people about stereotypes and biased language found in school materials

A guide for educators

Biased representations, including racist portrayals, gender stereotyping, and ableism, find their way into school textbooks with unsettling frequency. Teachers and parents have a responsibility to address these issues with students in the class and at home, but it’s not always easy.

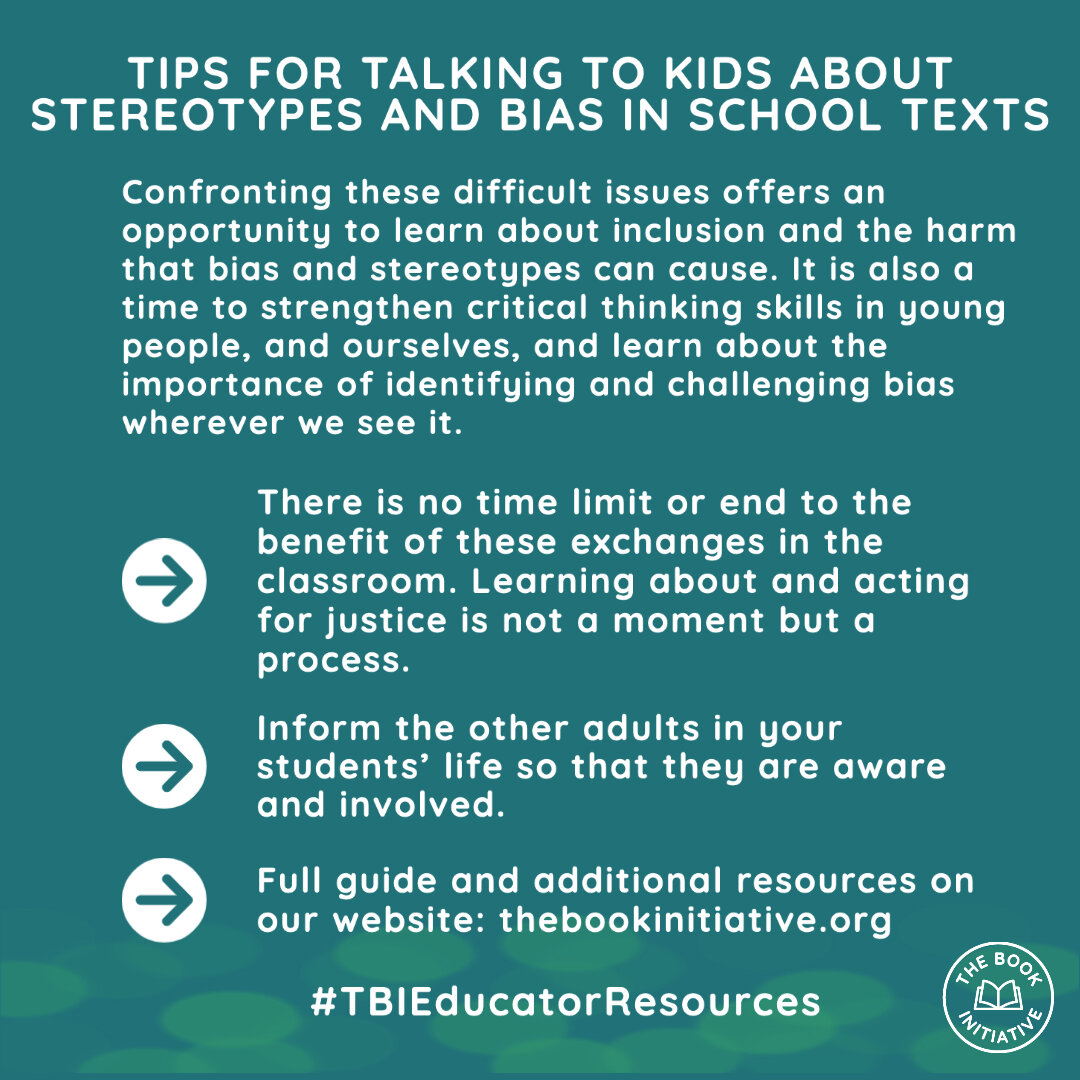

You may be tempted just to ignore or be vague about obvious problems in a text or image, or skip over it entirely. DON’T! Trusted adults must confront these issues with young people and discuss them openly and honestly. You also have an obligation to those who may have been harmed by the content to address it directly. And it’s not enough to just say it’s wrong – a conversation needs to take place. Make sure you inform the other adults in your students’ life as well so that they are aware and involved.

Confronting these difficult issues offers an opportunity to learn about inclusion and the harm that bias and stereotypes can cause. It is also a time to strengthen critical thinking skills in young people, and ourselves, and learn about the importance of identifying and challenging bias wherever we see it – even in “authoritative” texts.

This guide offers concrete advice about how to approach this conversation.

The Ten Slide Version:

Things to keep in mind

Make sure you are prepared before sitting down with your students.

If you need a few minutes or hours to be ready, that’s OK too. Acknowledge right away that the content is harmful and problematic and that a discussion needs to be had, but that it is an important discussion and you need time to think about doing it the best way. Ask for support or advice from colleagues or other adults if you need it. Don’t use this as an excuse to avoid the discussion.

Familiarize yourself with the language you may need – see our brief glossary at the end of this document.

Accept that your students, and you, will make mistakes. Use them for reflection and learning, not shaming.

Create a space for personal stories without putting students on the spot or asking them to speak for their identity group. For example, ask an open question of the group rather than calling on a specific student. Don’t assume individuals have had an experience or feel a certain way because of their (perceived) identity group.

You and the students may feel strong emotions during the discussion. It is OK to pause, take a deep breath, and think about how you want to continue. Allow students the time to do this as well. Distinguish between strong emotions and aggressive behavior. Expressing oneself honestly is OK; attacking others is not.

Allow for moments of silence within the conversation. These don’t need to be filled in.

Starting the conversation

Be positive, calm, and honest – young people pick up on body language. Model how to contribute and listen, and create a safe space for them to participate. If you are uncomfortable, that’s OK – these conversations can be difficult.

Explain to students what the conversation is going to be about: “There is a story/illustration in our textbook that is harmful, and I want us to talk about it today.”

Gain students’ agreement that conversations will be respectful. This means listening openly, no name-calling, and recognizing people as individuals. Avoid generalizations and model person-first and identity-first language (i.e., ‘someone who is Chinese’ or ‘Chinese people,’ not ‘The Chinese’). Paraphrasing is a good tool to help students improve their own language. For example, a student may ask, “Why do Whites always …?” You can paraphrase their question in your answer: “Sometimes, people who are White…”

Discourage repetition of any offending language in the text involved – it is OK to draw a red line through this language and tell students it is not to be used.

Begin with them

Start by gauging where the students are in their own knowledge, understanding, and reactions.

If you are addressing the content proactively (before any complaints have been made), identify the page(s) concerned and ask them if they are familiar with it. Give them time to read or look at it in silence and form some of their own ideas. If your conversation is taking place in response to a complaint or a news story, ask the class if they are familiar with the controversy and to share what they’ve heard about it. This is important for being able to meet them where they are in the process and correct eventual misinformation. Then give them time to read or look at the page(s) in silence.

It is also OK to continue a conversation about an issue that has been previously addressed. There is no time limit or end to the benefit of these exchanges in the classroom. Learning about and acting for justice is not a moment but a process.

Questions

What do you see happening in the text or image? Who is taking action? What are they doing?

Ask them to provide evidence for their answers – what are the specific words or images that lead them to their conclusions, and why? Sometimes what is missing is the problem. This is important throughout the conversation, and especially if it is an illustrated text – sometimes the words or pictures are not in themselves problematic, but it’s their placement together. It is crucial to learn how to make these critical distinctions.

Who has the power in the text or image? How can you tell?

Is there unfairness or injustice being portrayed? How can you tell?

What assumptions, misinformation, or biases are being used? Who is harmed by this? Who benefits from it?

Are there overt or subtle messages about the value of different cultural groups and backgrounds, origin, family make up, skin color, gender, ability, neurodiversity, or income? For example, is a character presumed to be good or bad at something or like certain things due to their group identity? Look at the language used: Do characters from a minority background speak in stilted dialogue? Are epithets or derogatory language used?

What would fairness, kindness, or justice look like in this situation?

How can you relate what is happening in this text or image to your own experience?

If students are comfortable speaking up of their own accord, they can share. But this can also be a moment of silent reflection.

Summarize

It is essential to summarize the conversation when it is over. Students and teachers will also need time to reflect and process emotions, reinforcing the lessons and building on what they’ve learned. Strategies can include small group or individual work and can be shared with the class or kept private.

Make sure you also leave space and opportunity for students to communicate their thoughts, experiences or concerns outside this discussion – in private or anonymously if needed.

Take Action

What can we do now, as a group?

Model activism by deciding together on an action plan that directly relates to the conversation and the aspects that resonated most strongly with the group. Make sure that, as a group, you vocalize the problem you want to address, the outcome you wish for, and how you think your idea will ontribute to this outcome. The project could be redrawing/retelling the story either as individuals or as a group; writing a letter to the people responsible for placing this text in the classroom (Publishers, Authors, Illustrators, but also Principals and School Districts) or a letter to raise awareness (to the other students at the school, to the parents at the school, to a newspaper or other public forum); writing up class guidelines for respectful language and images; or another action that combats bias and promotes justice. Allow the shape of the project to come from the students and their concerns – try to limit your role to facilitating the conversation and helping them to identify and resolve potential hurdles in their plan.

Some useful words to understand

Identity – a set of visible and invisible characteristics we use to categorize ourselves and those around us (e.g., gender, race, age, religion, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, language, family make up, immigration status/country of origin, ability, sexual orientation, etc.); identity shapes our experience

Identity group – a group that shares one or more identity characteristics (e.g., gender, race, age, etc.)

Dominant vs Non-dominant groups – a Dominant Group is a group with power, privileges and social status. A Non-dominant group does not have these advantages. A single person may simultaneously belong to dominant identity groups (e.g., straight, White) and non-dominant identity groups (e.g., undocumented, experiencing poverty)

Privilege – the benefits, advantages, and power given due to the social identities shared with the dominant culture

Stereotype - an often widely held but oversimplified image, idea, or unfair belief that groups of people have particular characteristics or that all people in a group are the same

Bias – conscious or unconscious personal preference for, or against, an individual or a group based on their identity

Discrimination – unfair treatment of a person or group based on their identity

Inferior – to be made to feel like you are less than others, that you have no value

Superior – to believe you are better than someone else

Social justice - commitment to challenging social, cultural, and economic inequalities that arise from any differential distribution of power, resources, and privilege; the view that everyone deserves to enjoy the same economic, political and social rights, regardless of identity or identity group